Ancient History

ANCIENT HISTORY

As the retreating ice sheets uncovered the bleak and barren surface of the land, sea levels rose and filled the yawning chasm that would, in time, become the Irish Sea. The time was approximately 11,000 years ago and, save a few migrating birds, neither flora nor fauna decorated the rocky, scree covered panorama. It would not be long, however before the first grasses would appear, and the length and breadth of the land shimmered under constant moisture-laden gales.

Within a few hundred years, forests of beech and juniper, alder and birch, would cloak the land, trapping the mists from leaden skies. The stage was set for the arrival of our earliest ancestors – those who would begin the process of transforming this land and capturing it’s shrouded mysteries as captivating tales of legend and myth. The Emerald Isle would at once be both beguiling and forbidding, and the reality no less fascinating than the myths themselves.

What would begin as storytellers art millennia ago would evolve into a record that approaches historical text. Never mere fancy, these legends can be viewed as markers of cultural change, and as such, they may provide a vivid, if exaggerated, glimpse of critical times of transition. Specific facts, such as names, dates, and even places must be treated with suspicion, but behind that façade often lays the framework of a civilization in evolution.

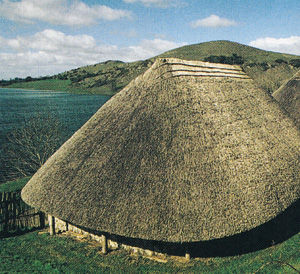

Neolithic man also left his physical imprint upon this land*1. This was The Age of Farming, and, as farmers, they cleared the land aggressively. With well-crafted stone axes they felled the forests that covered the highlands, and then the valleys. Wooden plows left imprints in the soil that have even been preserved to this day. They raised wheat and barley, pigs, goats, sheep, and cattle. The post-holes of supporting timbers for their homes are clearly evident at many excavations. Both round and rectangular structures are apparent. More permanent works of stone and soil marked burials, and as cairns and megaliths, they dot the landscape.

Standing stones of uncertain significance are almost as numerous.

Sophisticated scientific dating procedures confirm their presence from about 7000 B.C. onwards.*2 While the earliest visitors were Mesolithic hunter/gatherers, they were relatively small in number, maybe only a few thousand at their peak. It was the arrival of the Neolithic farmers in ~3500 B.C. that established the first enduring presence in Ireland. Monumental sites, such as the burial mound at Newgrange (~5200 years old)*3, and the legendary seat of the High Kings at Tara (~4500 years old)*4 confirm the skills and industriousness of these hardy folk.

As evidenced all over the world, the agricultural revolution, which began around 9000 B.C. at various points nearly simultaneously, was accompanied by a tremendous increase in population density. Indeed, it is just the fact of a fixed increase in food supply that caused the population explosion. Birth rates increased as children were no longer required to be mobile, and their value increased as additional “hands” to work the farm. It was more than five thousand years later that this revolution struck Ireland.

Ireland was generally the last point in Europe to receive most innovations because it was the last stop on the migration path. Because of that, and the relative isolation of the island, they retain the characteristics of ancient peoples most faithfully. Recent genetic analysis of Y-chromosomes from a cross-section of Irish men confirmed earlier work suggesting that the Irish retain the purest form of the haplotypes representing the most ancient Europeans. Those people originated about 30,000 years ago in the Near East, and arrived in Ireland well before 2000 BCE. The Connaught Irish retain 98 percent of this genetic marker, more even than the Basques, who retain 89 percent.*5 Other genetic analyses have added to our appreciation of successive tides of migration across Europe, bringing with them advancements in language, culture, and technology.*4 Great strides in etymological analysis has brought the study of languages, their origin and evolution, to a state of development enabling detailed comparisons with, and reinforcement of, discoveries in archaeology and genetics.*7 Taken together, and including legendary sources, a fascinating reconstruction of the life and times of these prehistoric peoples is becoming a reality.

The earliest legendary record we have of the progeny of those intrepid souls recalls them as the Partholans and the Formorians. They were probably non-IndoEuropean6 speakers, preceding the migration of the Celts by more than two thousand years. These Neolithic people were no match for the more advanced races that appeared in a steady stream over hundreds of years, beginning before 2000 B.C. The first of these were the Firbolgs.*8 They divided the island into the five provinces we know today. They also were responsible for the first monumental architecture – principally the fort at Dún Aonghus on the Aran Islands.

The Da Danann, legend tells us, were the first of the proto-Celtic tribes to arrive, subdue the Firbolgs in pitched battle on the plains of Sligo, and then be assimilated into their more numerous, vanquished host.9 The Da Dananns were reputedly Scythian in origin, and may have spoken a precursor to the Celtic tongue. These were Bronze Age warriors (ca. 1500 B.C.), and their weaponry must have been the deciding factor in the battle. The battle was not so one sided, however, and the Firbolgs retained the lands around the scene of the conflict, in present day Connaught. The scene of the battle is marked by dozens of commemorating cairns and pillars. Villages of these hardy souls were still reported in Medieval times.

The quasi-mythical appearance of the Firbolgs may coincide with the appearance of a unique pottery style – the “Bell Beaker” culture. It is found across Europe. Specimens have been dated to 2150 B.C. The numerous “Wedge Tombs” of the north and west of Ireland are also associated with this culture. “Stone Circles” also become common in this period. The Picts (later called the Cruithne by the Celts) may also have been part of this culture. Their origin is unknown.

In a similar fashion, the Da Dannan invasion may correspond to the archaeologically-defined Urnfield culture, so named for their burial method. Peoples associated with this culture had many of the traits of the later Celts.

At about 700 B.C. additional waves of displaced tribes began to appear. These invaders are the first to be recognized unambiguously as Celts. There were probably at least four waves, terminating in the Goidelic Celts, or Gaels14. They were driven from their homeland is what is now known as Germany, through France and Spain, to the shores of Eriu, the Celtic word for Eire, and later, Ireland during the first century B.C.. They were driven more by population pressure and internal competition than external threat at this point in time, although they had the expansionist Germanic tribes (Teutons) to their back. These Celts were probably remembered by later Irish storytellers as the Milesians, and their skills as warriors and administrators formed the basis for the political and cultural system that endured, in ever varied and modified forms, for the next 2000 years. Additional support for this connection with the coast of Spain is provided by the DNA work cited above.

Besides technology, the newcomers brought with them an even more enduring gift – the necromantic form of worship that would later be known as druidic.

The Celts were a loose association of tribes characterized by their lack of strong central leadership. Allegiance was to the clan of one’s birth, and the tuatha, or tribe. More than one hundred tuatha were present in Eire at various periods. At times, several tribes would ally themselves under a king, chosen by acclamation from among them. But these allegiances were fragile, ever shifting affairs, constantly disrupted by a pattern of internecine warfare. Their most common features were language and religion, but, even there, the widespread and fragmented nature of their association gave rise to numerous dialects and varied cultural interpretations.

The language spoken by the Celts was derived from an early branch of the Indo-European family, closest in structure to Italic, the precursor to Latin. This evolved into q-Celtic or Goidelic, and p-Celtic or Brythonic, forms, based largely on the substitution of those two letter sounds. The Goidelic form survived in Ireland to become Gaelic. Brythonic, the later variant, endured as the Welsh and Cornish tongues.

The Celts dominated Ireland like no previous culture. The previous pattern of assimilation by the indigenous culture was completely overthrown. The Celtic lifestyle pervaded every aspect of life, and moreover, resisted change by subsequent invaders for nearly 2000 years.

Archaeologists and historians refer to this early culture as the Hallstatt, after a relevant Austrian excavation site. This was the Early Iron Age, and the introduction of this tough metal transformed both warfare and farming, as well as the arts.

Rendering iron from it’s ore required much greater skill than the metallurgy of copper or bronze, and the high temperature furnaces employed had application in pottery, ceramics, and the later production of other useful products, like lime. Like the Celtic populations which remained on the European mainland, this culture progressed to a stage referred to as La Tene. The main features of this evolutionary step were a refinement of those already present : a greater sophistication in metalworking, more lavish adornments. Though, in this progression, the Irish yet again lagged behind their cousins on the continent – sometimes by 200 years or more.

If the early Celts were characterized by a sophisticated proficiency in technology, they were humbled by their deficiency in another crucial marker of civilization. The possessed no written language10. The later development of the cumbersome Runic script was prompted by exposure to the Latin alphabet, and the continental Saxons, and never rose to level of usage that would provide us with an adequate contemporary view of their culture.

As compensation for this inability to indelibly preserve their core cultural identity, the Celts raised oral traditions to a position of high respect. The storyteller, or fili, was accorded rank equivalent to the warrior or druid priest. In addition to a prodigious memory, the fili‘s creative talents established an early entertainment industry, developing a repertoire of prose and verse that would flourish centuries later.

The Gaels were divided into tribal nations, the North Gaels with their legendary seat at Tara, and the South Gaels, or Eoghanachs.

The rise of the Roman Empire in the last century BC had little impact upon the Irish. Even the conquest of Britain in 43 AD caused little change, except to enhance trade with the now subjugated Britains. Rome never seriously considered invading the barbarian island, and Rome’s departure in the fifth century only gave Irish raiders the opportunity to ransack the temporarily unprotected land.

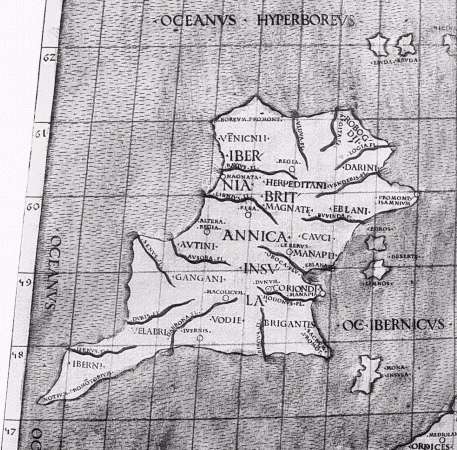

Ptolemy, the famous early geographer, recorded a view of the early inhabitants in ~150A.D., although the copy reproduced here is from 1490. Only a few of the tribes mentioned have been confirmed by later scholarship – which may only mean that they have been lost to time.

The earliest attempt to commit the oral traditions, histories, and genealogy of the Irish race to writing came in the 3rd Century A.D. with an edict of King Cormac Mac Art (who died in 266 choking on a fish bone) to commit the oral tradition of hereditary rule to writing. It was called the “Psalter of Tara” after the traditional site of Irish rule.13 It originally began with the three sons of Miletius, the pseudo-historical leader of the Milesians, and his issue. In the fifth Century, monks added a whimsical genealogical retrospective back to Adam. Although many historians believe that the recording is fairly accurate back to the fifth or sixth century, the hereditary use of surnames did not come into even limited use until the late 800’s and was not adopted by the general populace until the early 11th Century. This obviously forms a limit to the scope and precision of traditional genealogical work.

The Irish led the Europeans in the adoption of surnames by at least a century. This, combined with a rich tradition for composition of prose and verse, and the prodigious memory skills of the trained bards, helped preserve a cultural history unparalleled in the West. A large number of those tales survive.12 While the rest of Europe was entering the Dark Ages, Eire had discovered a calling. They would gather the retained memory of a civilization and commit it to paper (or vellum). They went on to practice their exacting, and richly ornamented skills all over Europe, and in the process, preserved the collective memory of western civilization.11

So thorough, and so voluminous, were the products of these master scribes, that not even the depredations of the Viking raiders of this age could erase the achievement. And the Vikings loved to target Monasteries.

Many of the legendary compositions begin with a recounting of the Milesian invasion.

Miletius allegedly had three sons who produced issue: Heremon, Heber, and Amergin (or Ir). Heremon ultimately killed his two brothers (or they drowned on the approach to the Irish coast), but their lines endured. The Mulvihill name owes it’s descendancy to the line of Heremon.

Over the next 1000 years the recorded legends detail a continuous, unrelenting period of tribal warfare. Rarely did one of the Kings listed in the Annals die a natural death, and succession was always an issue. The rules of the Age required leadership at the front in these engagements, and it was the royals (or aspiring royals) who suffered the greatest casualty. In fact, the common folk took little part in these affairs, as a rule. And when they did take the field in numbers, the resulting fight more closely resembled a brawl, compared with the set-piece pageants of later eras. When violence wasn’t being perpetrated in broad daylight, it was being orchestrated behind the scenes. This “bounty” of finely wrought sedition, seduction, and butchery provided the inspiration for Shakespeare’s portrayal of Eire’s later cousins.

It is at this point that we get the first glimpse of the start of the MaoilMhichil (Mulvihill) line.

In about 365 A.D. the 124th monarch of Eire, Eochaidh Muigh-Meadhoin died at Tara. He had four sons by his first wife, and one by his second (daughter of the Celtic King of Britain). This latter son, Niall, succeeded him as High King and would become one of the towering figures in Irish lore. One of the remaining sons, a prince of the realm named Brian, established a dynasty that continued through his great-grandsons, the Archdruid Ona, and MaoilMhichil, the eponymous ancestor to the Mulvihills. MaoilMhichil means “devotee of St. Michael.”

Niall was called “Niall of the Nine Hostages” due to the practice that he established during raids in Scotland, Britain and France during his reign. One of those hostages may have been a young boy later to become Saint Patrick. Niall was killed traitorously by an ally during a foray into France. It was also Niall that gave the name to Scotland (Scotia), using as a base the name that the Romans called the Irish - Scoti. The descendents of Niall formed a dynasty as the UiNeill.

Brian’s line came to be known as the UiBriuin, which, as the Clan expanded through the generations that followed, fractionated into many constituent tribes. They historically ruled the tribal kingdom (later Province) of Connaught, which included the north of County Roscommon. There, a small subsidiary tuatha, or tribe known as the Corca Achlann held territory. By 430 a MaoilMhichil, a chieftan of the Siol Muirdhaigh (SilMurray) parent clan group, shared the rule of the Corca Achlann (or Corca Seachlann) with Ona, whose descendents would form the MacBranan (Brennan) line. The Corca Achlann were part of a group of three tribes called the TriTuatha, and were vassals to the nearby, and more powerful, O’Conor clan. The other two tribes of the TriTuatha were the Tir Briuin na Sinna (led by the O'Monaghans, and later O’Biernes), the Cenel Dobtha (the O’Hanleys).

The territory of the Corca Achlann was bordered by the rivers Owenure and Scramogue , tributaries of the Shannon. It was approximately bounded by the present day towns (and past Poor Law Unions) of Carrick-on-Shannon, Strokestown, and Ballyclare.

The Corca Achlann were dominated by the MacBranans for much of their thousand year history, although their cousins, the O’MaoilMhichils shared power on occasion. As in all Celtic relationships, the extent and depth of the relationship between the two closely related tribes varied continuously. The MacBranans outnumbered the O’MaoilMhichils by a wide margin and so naturally commanded more authority. Mutual internal fractionation also complicates the picture. Almost certainly factions within both families allied themselves at various periods to conspire against other similar factions in the “extended family”.

Genetically, it would be expected that the descendents of these two tribes would be almost indistinguishable.

It is also very likely that remnants of the last Firbolg tribes still inhabited this area, especially in the nearby Slieve Bawn mountains. It is even more likely that the Milesian tribes in this area had incorporated a large part of the Firbolg gene pool. This may help to explain the results of the recent DNA analysis described above.

The island now has a population approaching 500,000, organized into about 150 tuatha, each led by a chieftan. These tuatha were banded together into more than two dozen different clan groups, also led by a chieftan, and was further organized into regional kingdoms and sub-kingdoms. Over all of these was the Ard Ri, or High King, seated at the legendary Tara. Contrary to modern Western sense of organizational order, the higher the rank, the less practical authority was conferred. The strength of the organization lay in the family and the family’s clan ties. All else was fugitive.

There were no towns. This was an agricultural society, and largely pastoral. Cow herds provided for the diet of largely dairy and meat, as well as being the favored means of exchange. Coined money was unknown. This was a patriarchal society of nobles and freemen, supported by slaves. Law was administered via the Brehon Code, providing for a variety of remedies, from fines to amputation, to killing. Hostage taking and giving, and fosterage, were a normal way of sealing transactions.

Given that this period is far too early to expect the hereditary application of surnames, the mention of MaoilMhichil might be considered coincidental. However, as we’ll see in the Historical period, the memory was preserved at least into the 12th Century. The exploits of later MaoilMhichils, and their continuing association with the Corca Achlann tribe, although sparse in the record, bespeak continuity if not absolute hereditary implications. It must be recognized, however, that the name may have been adopted by various unrelated, or at best, distantly related, individuals over the course of several hundred years leading up to the formal adoption of surnames in the 10th Century. Ultimately, however, the consolidation of MaoilMhichil into a hereditary surname, and the further Anglicization of the name to Mulvihill and Mitchell appears to be securely established.**

**No more can be said of these tales than that penned by the 9th Century Irish monk who wrote it all down:

“I, who copied this history down, or rather this fantasy, do not believe in all the details. Several things in it are Devilish lies. Others are the inventions of poets. And others again have been thought up for the entertainment of idiots.”*15

©Courtesy of James M. Mulvihill

No comments